When our country’s National Report Card was published last October, I was taken aback by the dramatic drop in our students’ math and reading scores since the beginning of the pandemic. The results were based on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) which has been used to evaluate education trends in our country since the 1990s. While the NAEP doesn’t tell us everything, it is a vital set of data for educators, particularly as we grapple with the impact the pandemic has had on our students.

While I think most educators expected a dip in scores, the magnitude of the loss was a lot to take in. I believe many of us had a similar response to the report as did our Secretary of Education, Dr. Miguel Cardona, particularly on these points:

- The scores are “appalling and unacceptable.” If the test results and calls to double-down on our recovery efforts don’t “have you fired up to raise the bar in education, this is the wrong profession for you.”

- “The data prior to the pandemic did not reflect an education system that was on the right track. The pandemic simply made that worse. It took poor performance and dropped it down even further.”

- There are some bright spots in the data. “65% of urban districts included in the NAEP showed no statistically significant decline in 4th grade reading scores, and 84% showed no such decline in 8th grade reading.”

- We must simultaneously meet students where they are while raising the bar for all students, not just in the immediate future, but in the long term.

- “Now is the time for bold action.”

We are fortunate that the Biden-Harris Administration jump-started improvement efforts via the American Rescue Plan (ARP), which gave states and school districts $130 billion to help students thrive. The ARP requires states, local districts, and public charter schools to have “meaningful stakeholder engagement” and to publicly post their planned use of ARP dollars.

While these efforts are to be applauded, and though the words above outline what politicians and others outside of the classroom must know, the ARP does not inform schools and teachers what WE must do to bring about urgent change, other than providing general guidelines.

Funding is just the beginning of what actually needs to happen in the day-to-day workings of schools. Funding won’t get us very far if we’re not in the trenches at schools and in classrooms doing the hard work to move us forward. Worse yet, if not utilized with intention and forethought, funding could be wasted on programs or services that are ineffective.

I’ve spent a good deal of time lamenting the results of the recent National Report Card, just as I’ve spent a good deal of time lamenting the many other losses our students carry with them, like missed graduation ceremonies, tournaments, and other important milestones. But, I’ve also spent a good deal of time wondering,

Now what? What are we (literally) to do in the classroom and in schools?

I think the first step is really one of mindset, a prerequisite for the plan I’ll outline shortly. We must take care when thinking about our students in terms of what they’ve lost during the pandemic. We risk creating a deficit mindset toward our students when, in reality, they possess countless skills, attitudes, and strengths that they bring to the classroom, some of which they gained during the pandemic (Honigsfeld 1-2). An assets based approach, where we start with the strengths of the students, rather than focusing on what may have been lost, is the best place to start.

The classroom is where the magic happens, so every plan for me comes down to its impact at the classroom level. Below I outline a 5-step plan that schools and districts can use while considering the basic systems and practices that apply to the classroom. This plan requires very little in terms of additional funding, making it possible to sustain improvement efforts over the longer term.

The path forward is within reach for all schools. Though there’s little about running a school or classroom that’s simple, I hope you’ll agree that the following guidelines are nothing new, they cost very little, and they don’t require us to do anything other than become more aware and intentional in our efforts to meet the needs of our students.

Develop a Literacy Ecosystem

A literacy ecosystem is “an interconnected group of individuals and activities that prioritize literacy development for all students, across disciplines, and beyond the school walls.” (Owen, 2022)

When a literacy ecosystem is in place, literacy becomes a communal priority, increasing the likelihood that literacy initiatives will succeed. As well, literacy ecosystems lend themselves to collaborative practices when literacy development among students is a joint responsibility.

To find out the degree to which a literacy ecosystem is present in your school or district, use this reflection tool as a starting point.

Rethink staff meetings

Staff meetings take time. Time we do not have. Time I could be spending on my classes.

Teachers don’t typically begrudge time spent in meetings when they know it will benefit them or their students. In fact, teachers are some of the most generous people on the planet when it comes to putting in extra time on behalf of the children and young adults in their charge.

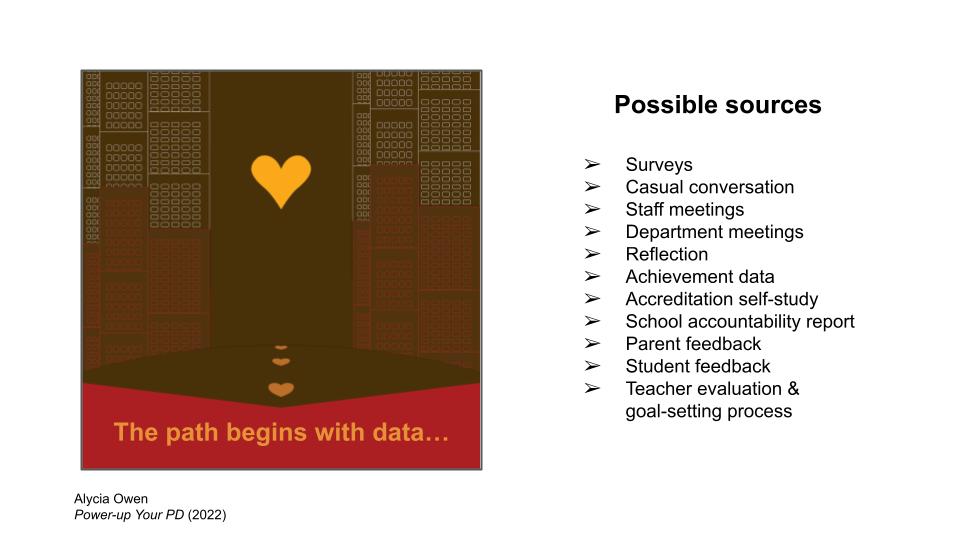

That being the case, I would encourage site administrators to 1) take a data-based approach to finding out what your teachers need, then, 2) act in good faith on what the data tells you. For example, if a quick online staff survey shows that many teachers have questions about translanguaging in the classroom, set aside time at an upcoming staff meeting to host a guided discussion on the topic. Or, ask a faculty member or two who are using translanguaging strategies effectively to share their knowledge.

In this way, meetings gain relevance and build capacity around topics of greatest need to those who work most directly with students. This is not to say that longer-term or administrative initiatives shouldn’t be addressed in staff meetings, rather that the content and structure of staff meetings should reflect the expressed needs of the staff members who are most directly impacted by the topics covered at those meetings.

Plan to SWiRL

If you’ve been working with multilingual learners (MLLs) in the past few years, you may be familiar with the acronym, SWiRL. It serves as a reminder to plan lessons that incorporate all language domains in a way that encourages student interaction. So, a SWiRLed lesson includes opportunities for students to speak, write, interact, read, and listen.

Applying SWiRL when planning to teach MLLs is critical for their success. After all, how does one learn a language without using it with other people? This being the case, let’s consider for a moment that ALL students, even native English speakers, use a different language at school than they use at home or with their friends. This ‘foreign’ language is academic English.

Unlike conversational English, academic English is characterized by highly specialized vocabulary that is used in very precise ways and in very specific contexts. For example, students in a high school science class might be asked to discuss the various reactions that take place in the Calvin cycle in photosynthesis. My guess is, most of these students won’t have very many reasons in their future lives to use phrases like light-independent reaction or atmospheric carbon dioxide. This is true whether or not the students are native English speakers or are learning a second or third language. All students are academic language learners, or ALLs.

Let’s broaden how we apply SWiRL to our lesson plans by considering that every student is working to gain fluency in academic English, not just those whose first language is something other than English. As we move forward, SWiRLed lessons should be the norm in all classrooms to ensure that academic language development is intentionally supported and developed across all language domains in lessons that encourage interaction between students. The days of lessons in which students ‘sit & get’ are relics of a past that has not served our students well and, if MLLs make big gains as a result of SWiRLing our lessons, we can use this knowledge to support all students in their pursuit of academic achievement.

Build in movement and hydration

It’s very concerning when districts reduce or eliminate activities like recess and PE as a way to ‘get back’ instructional time. While this tactic may seem like a fair trade on the surface, it’s not an effective course and could, in fact, be harming our kids.

For just a moment here, I’m going to become that teacher. The one who wants to return to the way it was when she was in school. Humor me, please.

When I was in lower elementary school, I would have been content to spend every recess with my nose in a book. I would have been happier still to stay in the classroom, especially on those days when Santa Ana winds whipped through my SoCal town. But our teachers made us go out to play. They made us participate in PE. And, when it was time to come back into the classroom, they made us stop at the water fountain to get a drink before the next lesson. They knew what was good for us.

We weren’t coerced or mistreated, of course, but our school leaders and teachers made sure that physical exercise and hydration were prioritized so that we could get the most out of our lessons when we were seated in the classroom. Our bodies’ physical needs were addressed so that we could do things that required lots of brain power.

Physical movement and hydration are necessary for our brains to work effectively, and they help us to stay focused when we’re doing something that requires cognitive effort. Movement has the added benefit of lowering stress. We would be wise to incorporate both into our daily school routines, if we want our students to succeed academically.

Connect with families

We typically invite our students’ families to join us for Back-to-School Nights, Parent-Teacher Conferences, or important meetings, but there’s so much more we can do to develop a strong partnership between schools and the families of the students we serve.

If you’re wondering whether it’s worth the effort, consider that family engagement in schools can lead to several positive outcomes including improved student achievement, fewer disciplinary issues, improved parent-teacher and teacher-student relationships, as well as a better school climate.

So, consider branching out when it comes to engaging families. Move beyond the typical parent meetings and consider making family connections a priority throughout the school year by incorporating a range of activities. There is not one right way to do it, but family activities across a school year, in addition to parent-teacher conferences, might include activities such as these:

Moving forward can be challenging, especially when the stakes are so high. But with a plan to structure our path ahead, we can do great things. I hope the 5 points illustrated here serve as a starting point for discussion and action in schools.

Wishing you all a very happy new year and renewed energy for the coming semester!

Alycia

References

Honigsfeld, Andrea, et al. “Establish Your Why.” From Equity Insights to Action: Critical Strategies for Teaching Multilingual Learners, Corwin, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2022.

“Impact of Family Engagement.” Impact of Family Engagement. Youth.gov, https://youth.gov/youth-topics/impact-family-engagement.

“Remarks by U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona on Nation’s Report Card.” U.S. Department of Education, 24 Oct. 2022, https://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/remarks-us-secretary-education-miguel-cardona-nations-report-card.

“Why We Should Not Cut P.E.” ASCD, https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/why-we-should-not-cut-p.e.